QUESTION:

What is the current status on malaria? And does P.knowlesi spp. pose a greater threat compared to the others? Does the number malaria cases increase every year globally? Is P. knowlesi spp. more dangerous than the others and why?

ANSWER:

I’ll answer your question about Plasmodium knowlesi first. So far, it is considered a relatively minor source of malaria in humans, as its natural host are macaque monkeys and so it is usually thought of as a “zoonotic” disease.Between 2000-2008, there were only been about 400 reported cases of P. knowlesi, all restricted to south-east Asia, and mainly Borneo. These figures are low compared to other forms of malaria, such as P. falciparum, which in Africa alone accounts for millions of cases a year, and close to a million fatalities. However, there are some causes for concern with regards to P. knowlesi.

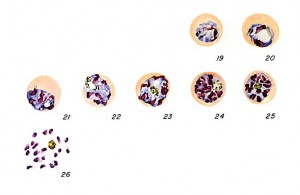

First of all, it appears to be an emerging human infection; the first cases were traced back to the 1960s, with the number of cases increasing in recent years. While some of this increase is likely the result of higher accuracy diagnosis and awareness about malaria, it is also hypothesised that the increasing population density in forested areas of south-east Asia may also be leading to greater numbers of people being exposed to this parasite. Secondly, although easily treated with anti-malarial drugs, the life cycle of P. knowlesi is such that it reproduces very rapidly in the human host, causing cycles of fever every 24 hours (a so-called “quotidian fever”). This means that the infection can progress rapidly, becoming severe in a matter of days, and therefore requiring prompt treatment. Finally, although locally restricted to south-east Asia, P. knowlesi has become the dominant form of malaria in some of these areas, notably Sarawak. As such, although currently not a major source of malaria in the global human population, it is locally important to public health and moreover, more research is needed to determine why the number of cases has been on the rise.

As for your questions about the status of malaria globally, the number of cases annually is estimated to be around 250 million. The vast majority of these are in Africa. Over 700,000 people, mainly children under five, die from malaria each year. As for whether the number of cases is increasing or decreasing, this is hard to determine. For one, a large number of cases are not reported every year, making accurate estimates difficult. Secondly, the world’s population is growing, and it is growing at the greatest rate in Africa, where the majority of malaria cases occur. As such, even if the proportion of people with malaria decreases over time, due to health initiatives such as distributing long-lasting insecticide treated bednets or free treatment, the total number of cases may still rise. Another problem we face in the fight against malaria is climate change: as the world’s patterns of rainfall and temperatures change, new areas become susceptible to malaria transmission, putting more people at risk. However, what is very encouraging is that deaths from malaria seem to be decreasing on a global scale.

Malaria No More is an organisation dedicated to eliminating deaths from malaria by the year 2015; more information about their methods and some of their success stories can be found on the Malaria No More website.