In November 2012, the Board of the Global Fund meets to determine the future of the Affordable Medicines Facility – malaria. Should it be cut, to make better use of limited funds? Or does it still have a role to play in the fight against malaria?

In late 2009, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (hereafter, the Global Fund) launched an initiative called the Affordable Medicines Facility – malaria (AFMm), designed to improve access to artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) to malaria endemic countries. The motivation for the facility was two-fold: first of all, there was a realization that the current prices of ACTs were prohibitive for most inhabitants of malaria-endemic countries, particularly if they sought health care via for-profit private clinics. Secondly, in contrast to the high price of ACTs, artemisinin monotherapies were widely available and much more affordable, leading to fears about the emergence of resistance. ACTs are thought to be more robust against resistance, and so by lowering the price, the AMFm hoped to improve market share against monotherapies, and also make ACTs more widely available to developing country populations.

The mechanism decided on by the Global Fund was relatively straightforward. The AMFm would negotiate with the manufacturers of ACTs and pay them directly a proportion of the cost of the drug. The remainder, roughly 20% of the total in most cases, would then be paid for by whole-sale drug distributors in target malaria-endemic countries, many of which are in sub-Saharan Africa. As they were able to purchase the drug at low cost, these whole-sale distributors, many of which were in the private sector, could still make a profit without passing on prohibitive costs to their customers. As mentioned above, the hope was that this would increase local people’s ability to purchase ACTs, and move them away from the less effective monotherapies that were also available. The first trials of the scheme were started in early 2010; now, less than three years later, the Board of the Global Fund is poised to decide whether the AMFm should continue in a modified form, or, due to wide-scale funding shortfalls, it should be abandoned entirely.

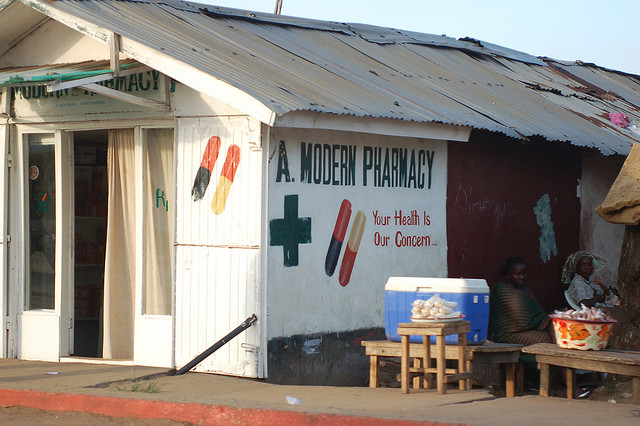

A small-scale, for-profit private sector pharmacy in Liberia. Such pharmacies supple a large proportion of anti-malarial drugs in some countries in sub-Saharan Africa (Photo courtesy of Erik Hersman, via Flickr).

Of course, the overall aim of the Global Fund is to reduce malaria morbidity and mortality, and the mandate of the AMFm is along the same lines; however, such an outcome was never going to be a plausible metric in the few short years since the facility’s inception. So how should the success of the AMFm be judged? Two papers [1,2] were published in this week’s issue of Science magazine, one of the world’s leading scientific journals, shed light on the achievements of the AMFm, though without shying away from some ways in which it has perhaps fallen short. Overall, both recommend the future continuation of the AMFm, albeit with changes to its remit.

One way in which the effects of the AMFm can be judged is through studying ACT availability in different markets in the countries which received subsidized medication. Overall, most research seems to have demonstrated that ACT availability has increased, and particularly in rural areas and in the private sector. However, in many countries surveyed, monotherapies were also still available, maintaining fears that artemisinin resistance could arise in Africa, as it appears to have in parts of Asia. However, just because medications are available does not mean they are being taken appropriately, and this is a key point made by both sets of authors.

Indeed, the analysis by Cohen et al. suggests that in many settings, the market for purchase of ACTs is much larger than the actual need, based on the number of people seeking treatment for malaria in the private sector versus the actual numbers of malaria cases. While this is good news for the private sector, in terms of making profits from sale of malaria treatment, it also implies that overtreatment remains a large issue, and thus the subsidy provided by the AMFm is not being put to the best use. Of course, the scale of this issue varies from country to country; those with high malaria endemicity probably have lower rates of overtreatment since more people are likely to require treatment; likewise, younger children (particularly those under the age of five) are more likely to have malaria than adults, and so overtreatment is less of an issue in this age group. I have mentioned overtreatment in previous blogs as a potentially enormous problem in many parts of Africa; both authors make it clear that addressing the issue of overtreatment is crucial is determining a future direction for the AMFm.

A promising avenue of engagement for reduced overtreatment is through improving diagnosis. Therefore, the authors suggest, the AMFm could seek to reduce its involvement in providing subsidies for countries with high levels of overdiagnosis. Instead, in these settings, the money could be redirected into providing affordable malaria rapid diagnostic tests (mRDTs), which are extremely effective, easy to use, and provide an accurate indication of whether malaria treatment is actually required. For countries with lower rates of overdiagnosis, subsidies could continue, though one way of making them more effective could be to pass the price negotiations into the hands of the whole-sale drug distributors, rather than being handled exclusively by the Global Fund. The AMFm could still step in to fill pricing shortfalls, but letting individual companies lead the negotiations will improve outcomes, and also improve long-term sustainability of the program: as countries become more developing, AMFm can slowly reduce funding, allowing the market, and the populace, to step up their investment.

A typical lateral flow malaria rapid diagnostic test. These tests may fill a crucial role in improving diagnosis of malaria, particularly in areas where overtreatment is rife (Photo courtesy of Prashant Panjiar at the Gates Foundation, via Flickr).

The issue of diagnosis also brings forth a broader point, which is that of integrated management of disease, another topic I have discussed before, though previously in the context of neglected tropical diseases. In these papers, both authors make a point to mention that fevers in malarial countries are not always caused by malaria; the use of mRDTs can help elucidate when malaria is not the cause, but it does help when it comes to finding out the actual cause of illness. Instead, countries, and, by association, development donors, should look ahead to promoting integrated management of febrile illnesses. This way, as efforts to combat malaria continue, and continue to be successful, health systems will be ready to deal with the changes in proportion and prevalence of other diseases, as malaria becomes less of a leading cause of morbidity and mortality.

References

- JM Cohen, AM Woolsey, OJ Sabot, PW Gething, AJ Tatem & B Moonen (2012). Optimizing Investments in Malaria Treatment and Diagnosis, vol. 338, no. 6107, pp 612-614.

- R Laxminarayan, K Arrow, D Jamison & BR Bloom (2010). From Financing to Fevers: Lessons of an Antimalarial Subsidy Program, vol. 338, no. 6107, pp 615-616.