For many years the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) have been promoting an Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) training package to ensure that nurses and doctors are capable of treating sick children at health facilities. Over the years, with the realization that many children did not have access to health facilities and therefore were not being ttreated, the two organizations published a Joint Statement on Managing Pneumonia in Community Settings (2004)[1]. This groundbreaking document calls on countries to bring treatment of childhood illness – pneumonia as well as malaria and diarrhea closer to communities that need it, by empowering trained community health workers to identify and manage these problems. Many countries have followed this advice with excellent results. Here is a story from Ethiopia.

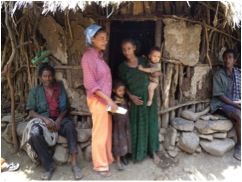

Aminata is a health extension worker (HEW) at the Tebisa health post, located in a rural, hilly area of East Amhara, some 400 kilometers away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. Aminata received training on integrated community based management of common childhood illnesses (iCCM) in early 2011. After the training, she carried the essential materials and supplies with her back to the health post, and started treating children suffering from pneumonia, malaria, diarrhoea and/or severe acute malnutrition. In the last two months, she has treated 35 children under five.

One of the children suffering from malaria is a five year old girl, Almaz (which means diamond in Amharic). She developed fever one night in April. Her mother took her to the health post and she was seen immediately. Aminata checked her temperature (39.0 OC), and respiratory rate (children sometimes have pneumonia and malaria at the same time) and pricked her finger to obtain a drop of blood to perform a Rapid Test for Malaria (RTM) to look for malaria parasites [Ed: Rapid Diagnostic Tests, or RDTs, are another, more general term for these tests].

Almaz did not have rapid breathing, an indication of pneumonia, but she did have falciparum malaria (the most severe and deadly of the types of malaria found in humans, and caused by the Plasmodium falciparum parasite). She was given Coartem (Arthemeter-Lumefentrine) treatment by mouth for three days. Aminata gave the first dose of medicine and gave the mother the rest of the tablets, explaining when to give them. Aminata made a point to discuss how important it is to feed a sick child so they do not lose weight, and to be alert to certain ‘danger signs’ in case the child is not getting better, in which case they should return immediately to the health post.

On the second day of treatment her mother brought her back to the health post for a follow up check. Almaz’s mother expressed her gratitude. “If the HEWs are not providing treatment for sick children, I would have to carry Almaz to the health center some 4 hours away by foot. I would also have to pay for the treatment. We were frustrated before iCCM started because we were not able to help children with malaria and pneumonia”.

“The communities trust and support us even more now”, said Aminata. “Now the mothers are so happy, they even bring the children for immunization without us having to push them”.

In the next two years, about 20,000 HEWs will be trained and supported to provide iCCM in 10,000 rural villages. Hundreds and thousands of young children in Ethiopia will benefit from the iCCM programme jointly supported by the government of Ethiopia, Catalytic Initiative of Canada, UNICEF and other development partners. Program implementation will focus on remote and harder to reach villages and households, to ensure every child is covered, no matter where they are and who they are.

The iCCM is be an important opportunity to further improve quality of care provided at the health posts, and accelerate toward the achievement of Millennium Development Goal 4, to reduce deaths of children under 5 by two-thirds by 2015.