QUESTION

Where is malaria found?

ANSWER

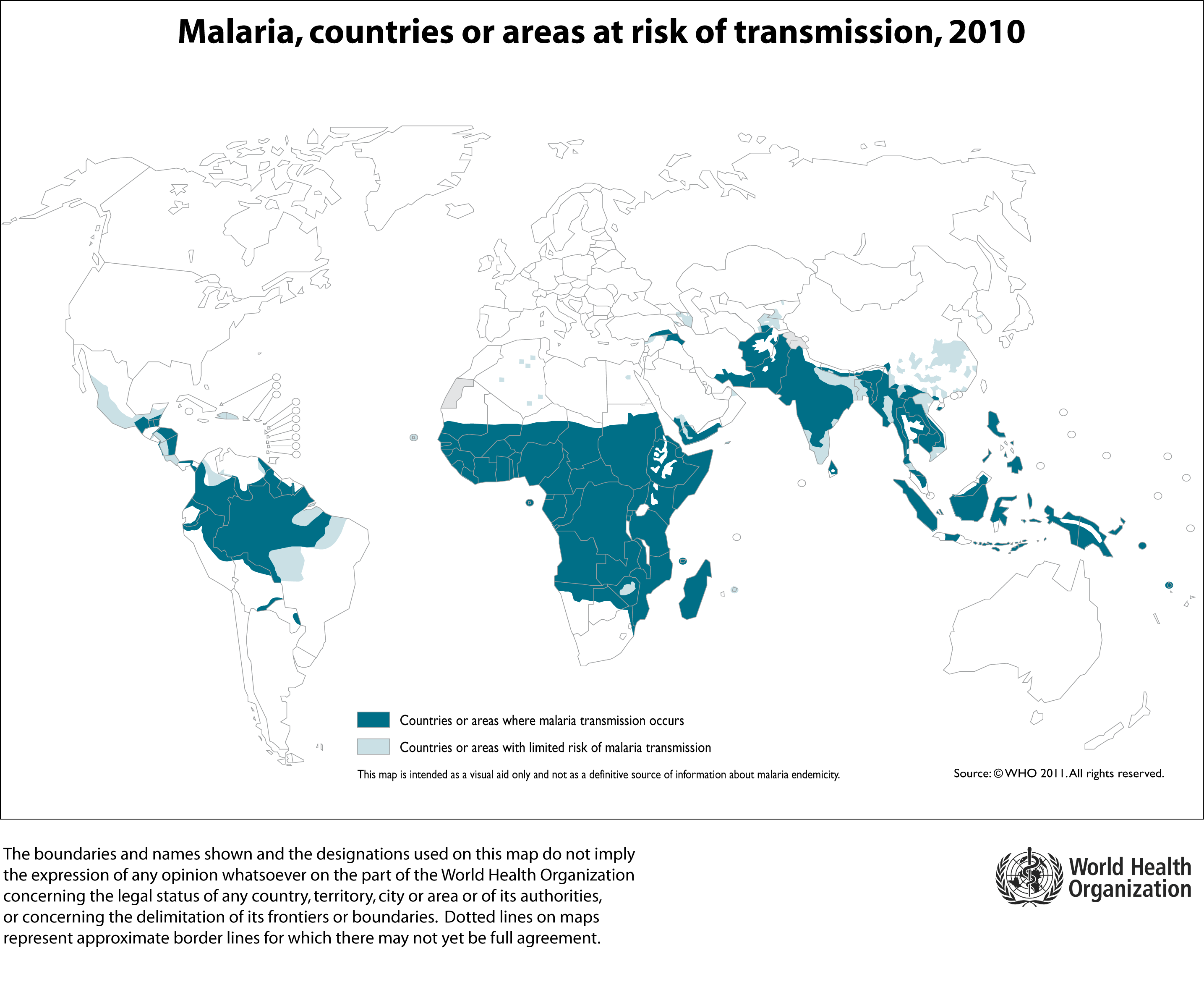

Malaria is found throughout the world’s tropical and sub-tropical areas, and mainly in Central and South America, Africa, Asia and the Indo-Pacific region. It is most common in tropical regions, where transmission occurs year-round; in sub-tropical and temperate areas, transmission may only occur during seasons that have appropriate climatic conditions. This includes sufficiently high temperature and water availability for the growth and development of the mosquito, which transmits the disease. Currently, the greatest burden of the disease is felt in sub-Saharan Africa, where over 90% of deaths due to malaria occur. The map below shows the estimated risk for malaria across the world, courtesy of the World Health Organisation.