QUESTION

Has the geographic range of malaria increased over the past 20 – 30 years? I have read that preventative measures have helped lower rates of infection, but I’m interested in the extension of the range itself.

ANSWER

That is a very interesting question, and one that garners quite a lot of debate. Preventative measures have actually also helped to limit the range of malaria globally. For example, malaria used to be relatively common in the Mediterranean basin and south-eastern United States, but control measures (mainly based around killing mosquitoes and removing suitable mosquito habitat) has largely eradicated malaria from these areas.

However, there is concern that on-going and future climate change has and will change the distribution of malaria globally. For example, some predictions have suggested that malaria might be able to re-establish itself in the Mediterranean and Middle East, due to higher rainfall and higher winter minimums of temperature. Additionally, malaria may be able to spread to higher altitudes in areas where it is already present at low elevations. This is of huge concern in places like Kenya: Nairobi, the capital city (with around 5million people), sits at 1660 m altitude, and as such currently has generally negligible levels of malaria transmission. However, if climate change enables malaria to move up to this altitude, a huge number of people will be at additional risk of infection. Worryingly, there is some evidence from the Kenyan highlands that these changes are already underway.

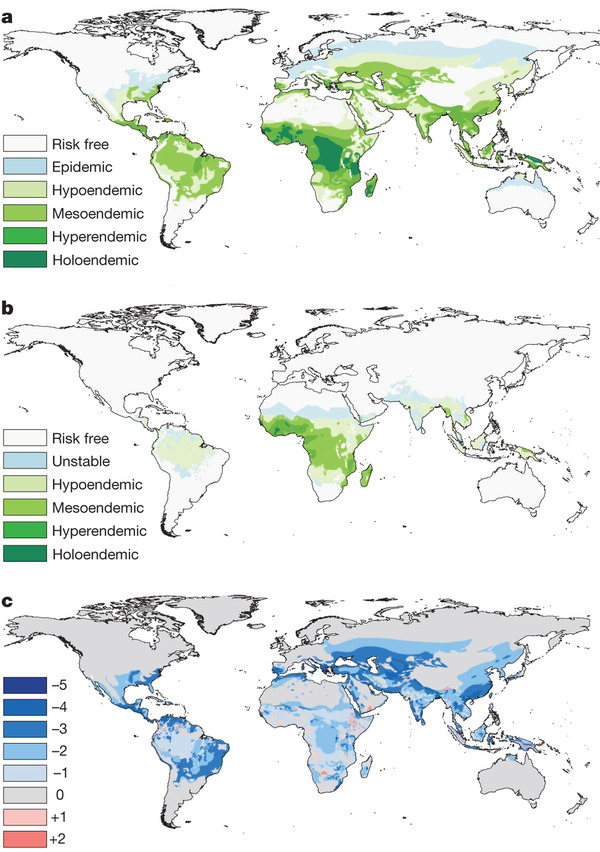

Having said this, there are also parts of the world which might see malaria transmission ease as a result of climate change. This is particularly the case where rainfall is expected to decrease, or change significantly in relation to temperature. Moreover, some scientists think that on-going control efforts, particularly with respect to the distribution of bednets, vector control and greater coverage of diagnosis and treatment will continue to reduce the geographical spread of malaria over and beyond the changes associated with climate change. These scientists have compiled a map of Plasmodium falciparum transmission now as compared to data from before control interventions were rolled out—the reduction of transmission risk in many parts of the world, are clear to see (see below).

Maps showing changes in transmission risk and endemicity of Plasmodium falciparum malaria between approximately 1900 (a) and now (b). (c) shows the balance of change in malaria transmission between the two time periods: the higher the negative number, the greater the reduction in malaria transmission. A positive number indicates increased malaria transmission. The different classes of malaria transmission risk are as follows: hypoendemic, prevalence < 10%; mesoendemic, PR ≥ 10% and < 50%; hyperendemic, prevalence ≥ 50% and < 75%; holoendemic, prevalence ≥ 75%. Image reproduced here from Gething et al., (2010), 'Climate change and the global malaria recession', in Nature, volume 465, pages 342-345.